A handmade brush is the burnt stick with hair tied to it—birch or beech carved and lacquered, a nickel-plated brass ferrule crimped and glued, and a tuft of honest hair: kolinsky for a needle point, hog bristle for muscle, squirrel for flood. That’s the tool. The mark comes from the hand, sure—but the meaning comes from someplace higher. As Sir Joshua Reynolds put it: “But it is not the eye, it is the mind, which the painter of genius desires to address.” (Third Discourse.)

This thought has been with me since the first day I used ChatGPT: this is the greatest time in the history of mankind to be an Artist, and it’s all because of Artificial Intelligence.

Let me set this up a bit. I was trained as a traditional artist during the “Desktop Revolution” of the 1990s. This “Revolution” was the introduction of digital tools like Photoshop. What made it a revolution is that now a single designer could make everything themselves, because the tools could all be run from a single workstation—mainly the Mac. The first of the “artists” that emerged in this new art form were people interested in the technology. They had this beautiful tool (the Mac), and now they could create beauty. This interested me a lot. I loved art and took all of my electives in high school as art classes (Santa Fe High, SF NM).

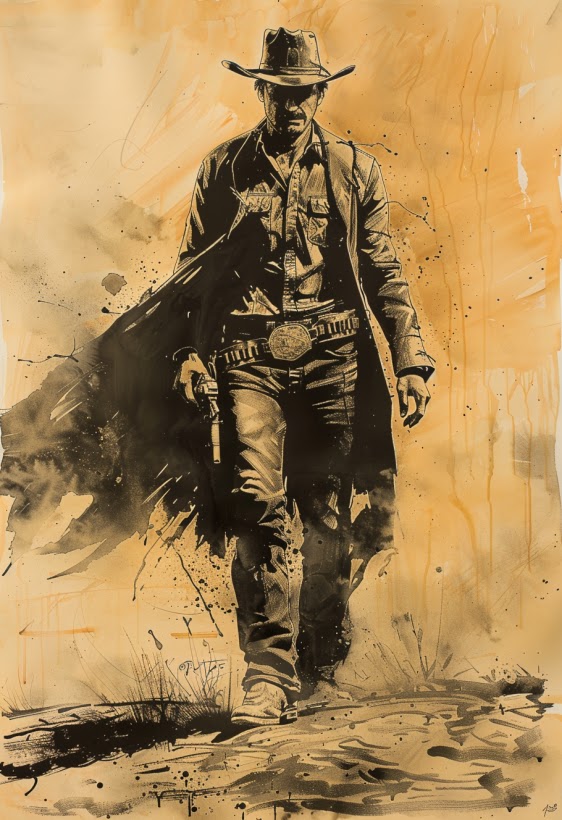

I met my mentor, Scott Kuntz, in college learning Adobe Illustrator. Scott was a traditional illustrator and I would consider him one of the last American illustrators in the tradition of Howard Pyle. Scott saw the value and interest in the digital tools, but with a lot of disdain. His gripe was always that it needed to look like traditional media. To build a picture of what I mean, Scott dedicated hundreds of hours to making traditional comic book inking come to life in Adobe Illustrator (v.4). He developed a method that I used for years after.

Anyway, learning from Scott, I picked up traditional watercolor painting in the tradition of John Pike (another badass American illustrator). I also learned how to do traditional comic book inking using the good old Winsor & Newton Series 7. (If you know, you know.)

This all helped me start building my taste for the greatest artists in time. And, buddy, it ain’t the Impressionists—though they are a close second for me. It’s the great American illustrator. Looking over these men of exceptional talent and skill, I was awed. They picked up the Grand Tradition from the Masters and made a Sears catalog, The Saturday Evening Post, and the great American comic book.

While the modern/postmodern movement was playing with psychology and nihilism—destroying everything they touched—our time-honored traditions were saved from annihilation in an unlikely spot: advertising.

Obviously these men, like Andrew Loomis, pointed toward where they learned the art form. And we can follow their gaze into the past and see who is to be followed and who is to be forgotten. The Grand Tradition was put in their capable hands. And thus we had a path to follow and a way to see it. And by “it” I mean BEAUTY.

Beauty is real and it is knowable, and as Charles Hawthorne—the watercolor painter (American illustrator)—says in this book of his quotations collected by his students, Hawthorne on Painting:

“Anything is beautiful if you have the vision—it is the seeing of the thing that makes it so.” —Charles W. Hawthorne

That’s the secret, you know, to becoming a truly great artist. Do you know what it is? It’s learning to see beauty and recognize it in its endless forms: music, theater, dance, love, violence, passion, brutality, kindness, and the occasional hilarious meme.

You see, no matter the burnt stick you are using to produce your expression, you really only have two options: keep it simple or make it beautiful. That’s the rule.

Simple, you say? Yeah—simple. “Do the simple thing before the superhuman” was also one of Hawthorne’s rules. You have only one other option besides beauty: simplicity.

Think of it this way. Have you ever seen JAWS? The first one. (Burn the rest.) Jaws is a great film, and it is great because it is simple. It has a perfect structure, beat by beat. It’s not shot in a very elaborate way—aside from their expert craftsmanship shooting on the Orca, handheld. The characters are classic archetypes. It’s a variation of Moby-Dick. And the whole thing is done in the primary triad—red, yellow, and blue. Simple. Anyone can get it. But it can still be a bit profound.

Beauty is Citizen Kane. It is intricate, deep, shot in a dramatic, sometimes jarring way. The plot is introspective, human-soul centered; the stakes are unclear, but you feel the weight of them immediately. The characters are real—faults, attributes, and evil are so deeply portrayed. That movie set the tone for the entire medium. And it still does. Welles was like, “Beat that, you pansies!” Has anyone?

With that type of standard in mind, it is much easier to see what the artist’s job is and how to do it right.

Enough with the lessons. What I’m getting at is this: if an artist truly understands what beauty is and how simplicity works, then the “burnt stick”—a.k.a. the tool—is irrelevant. The imprint of the artist is what humans respond to. Humans are the audience—nothing else. And only humans can recognize simplicity.

Only humans can see Beauty.

W.