Gotta love actors telling us about the world. Preaching from press junkets like prophets on the mount, handing down insights like scripture—usually written by their PR teams.

But I don’t blame them. The real crime isn’t that celebrities are full of themselves—it’s that the industry they represent has gone hollow.

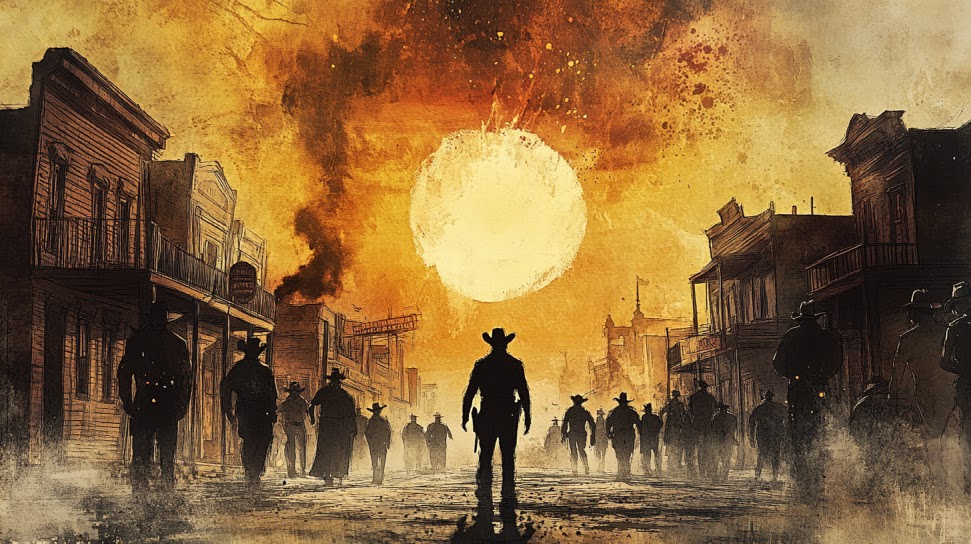

I was watching a recent interview with Ben Affleck and Matt Damon. These guys aren't just faces; they’re writers. They’re "men of ages" in this business. And they admitted something terrifying. They talked about how streaming giants are literally telling creators: "Give us a big explosion in the first five minutes so they don't click away," and "Repeat the plot in the dialogue three or four times because we know the audience is looking at their phones."

That is the state of the art. Most TV? Unwatchable. Most films? Even worse. Not because the craft is gone—there are still budgets, still talent, still tools that would make Eisenstein weep. No, what’s gone is depth. What’s gone is the basic respect for the audience.

Hollywood doesn’t think you’re dumb. It knows you are. Or at least, it bets that you are. Dumb, distracted, scrolling. Too glued to your phone to notice plot holes, too trained by TikTok to linger in a shot, too numbed out to care about anything that isn't loud or easy.

And that assumption bleeds into every frame. They don’t craft stories—they manage attention spans. It’s not about narrative; it’s about dopamine.

But cinema wasn’t always a content mill. I keep hoping for that shock of truth. Like in Lawrence of Arabia, when Lawrence crawls out of the desert, half-dead, half-transfigured. He reaches the Suez Canal, and a soldier on a motorcycle—the first sign of "civilization" he's seen in weeks—screams across the water: “WHO ARE YOU?”

Lawrence can’t answer. Not because he can't speak, but because he doesn’t know anymore. He’s confronted by the enormity of himself, and he’s speechless.

That’s the moment. That’s what storytelling was built to do. It’s supposed to strip you down.

Hitchcock understood that. He crafted films for people who noticed, who thought, who felt. He planted a spare key in Psycho—not just for the plot, but for the questions. He gave us Shadow of a Doubt, where the horror isn't a monster, but the cold realization of what humanity is capable of.

Remember the dinner scene? Uncle Charlie is laying out his nihilism, and his niece, desperate to cling to her innocence, cries out, "But they're human beings!" And he just looks at her. Cold. Empty. "Are they?"

Or look at Citizen Kane. When Kane walks out of that room after Susan leaves him, he passes between two mirrors. For a second, we don't see one man; we see an infinite corridor of Charles Foster Kanes—reflections of reflections. Orson Welles was telling us: You’ve watched this man for two hours, and you still don't know him. You only know the versions of him.

Compare that with today’s content mills, where exposition is delivered like a PowerPoint and characters exist to explain the theme out loud. Where silence is scary because someone might look away.

Here’s a radical thought for the creators, the game designers, and the writers: Maybe we earn back our audience by respecting them. Assume they’re smart. Assume they’re haunted by the same questions we are. Assume they notice the "spare keys" we hide in the narrative.

And maybe then, just maybe, we get back to the kind of cinema that demands you answer the only question that matters:

Who are you?